שיר השירים

הקדמה

קדש הקדשים

שיר השירים שחיבר שלמה המלך תופס מקום מיוחד בכתבי הקודש. אף שזו אחת משנים עשר יצירות במכלול כתבי הקודש (כתובים), התנא רבי עקיבא (שעליו אמרו בגמרא[1] וכולהו – כל חלקי התורה שבעל פה שנמנו שם – אליבא דרבי עקיבא) אותו רבי עקיבא הצהיר “שאין כל העולם כלו כדאי כיום שנתן בו שיר השירים לישראל” (משנה ידיים ג, ה). יתר על כן, הוסיף רבי עקיבא (שם), “שכל הכתובים קדש, ושיר השירים קדש הקדשים!”

המדרש[2] מציע משל שתעזור לנו להבין את דבריו של רבי עקיבא: א”ר אליעזר בן עזריה למה”ד למלך שנטל סאה של חטים ונתנה לנחתום וא”ל הוצא ממנו כך וכך סולת כך וכך סובין כך וכך מורסן וסלית לי מתוכה גלוסקא אחת יפה מנופה ומעולה. כך כל הכתובים קדש ושה”ש קדש קדשים. זאת אומרת שזו החכמה האלוקית הכי מזוקקת ומעודנת שיש.

על זה העמיד הזהר הקדוש[3] שאלה נכונה: “ואי תימא אמאי איהי בין הכתובים [במקום להיות בין ספרי הנביאים]? ומתרץ הזהר שם: הכי הוא ודאי, בגין דאיהו שיר תושבחתא דכנסת ישראל קא מתעטרא לעילא, ובגין כך כל תושבחן דעלמא לא סלקא רעותא לגבי קודשא בריך הוא כתושבחתא דא”.

ומוסיף ע”ז הזהר הקדוש[4] “יומא דאתגלי שירתא דא [שה”ש], ההוא יומא נחתת שכינתא לארעא, דכתיב (מ”א ח, יא) ולא יכלו הכהנים לעמוד לשרת וגו’, מאי טעמא, בגין כי מלא כבוד ה’ את בית ה’, בההוא יומא ממש אתגליאת תושבחתא דא”.

ואכן אנו מגלים שכאשר הסודות והרזין של שיר השירים התגלו בפני רבי עקיבא, בכה מאד, וכמו שכתב הט”ז[5] – “שמצאו תלמידיו של רע”ק שהיה בוכה בשבת ואמר עונג יש לי. ונ”ל דהיינו שמרוב דבקותו בהקב”ה זולגים עיניו דמעות שכן מצינו ברע”ק בזוהר חדש שהיה בוכה מאוד באמרו שיר השירים באשר ידע היכן הדברים מגיעים”.

והסיבה לכך – שההתגלות האלוקית בשיר השירים גדולה יותר ממה שהשכל – אפילו שכל הקדוש של רבי עקיבא – יכול להכיל[6].

אין זה פלא איפוא, ששיר השירים נחשבת לקדש הקדשים.

כל התורה כולה

אף על פי ששיר השירים כולל רק שמונה פרקים, וגם הם קצרים למדי, הזהר הקדוש[7] מצהיר ש”איהי כללא דכל אורייתא, כללא דכל עובדא דבראשית, כללא דרזא דאבהן, כללא דגלותא דמצרים, וכד נפקו ישראל ממצרים, ותושבחתא דימא, כללא דעשר אמירן, וקיומא דהר סיני, וכד אזלו ישראל במדברא, עד דעאלו לארעא, ואתבני בי מקדשא, כללא דעטורא דשמא קדישא עלאה, ברחימו ובחדוה, כללא דגלותהון דישראל ביני עממיא, ופורקנא דלהון, כללא דתחיית המתים, עד יומא דאיהי שבת לה’. מאי דהוה, ומאי דהוי, ומאי דזמין למהוי לבתר ביומא שביעאה כד יהא שבת לה’, כלא איהו בשיר השירים!”

מאיפֹה למד שלמה המלך כל זה? הסביר רבי שמעון בר יוחאי[8] שהוא רכש את כל הידע הכלול בשיר השירים מהמלאכים הגדולים. לפיכך, אל תקראו את השם של השיר ‘שִׁיר הֲשִׁירִים’, אלא ‘שִׁיר הֲשַׂרִים’ – השיר שֶׁהֲשַׂרִים – המלאכים הקדושים ביותר למעלה – שׁרים (האמנם שאפילו מלאכי מעלה לא מבינים את עומקו, כמו שיבואר לקמן).

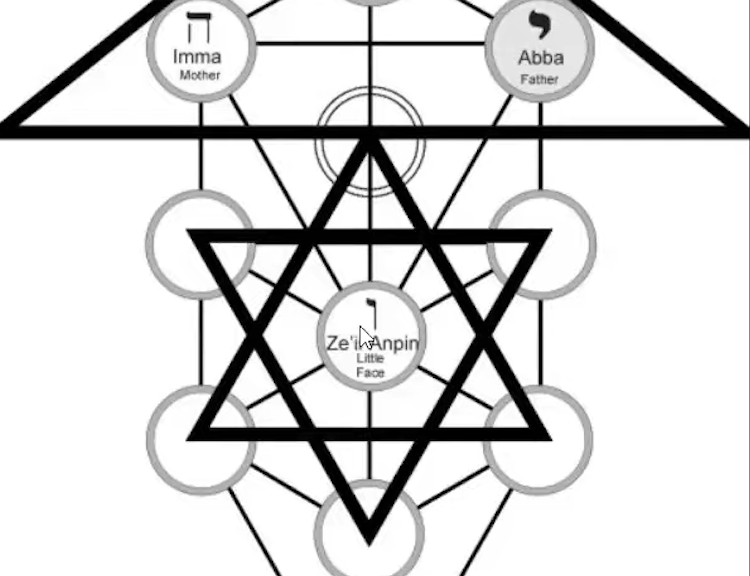

מרכבה

שמא נחשוב ששיר השירים מספקת לנו רק את הכתוב כאוצר נשגב אך בלום ואף נסתר, והמפתחות לפתיחתו אין לנו, אומר על כך הזהר הקדוש שכשרצה הקב”ה לחשוף את סודות שיר השירים עלי אדמות – סודות שהקב”ה לא גילה אפילו למלאכי מעלה, כלומר החכמה הסודית של השם המפורש וכל השמות הקדושים הנובעים ממנו – גילה אותם הקב”ה בעצמו לשלמה המלך. באותו זמן המלאכים הכריזו, “מה אדיר שמך בכל הארץ…” (תהלים ח, ב)[9].

ובמקום אחר מצהיר הזהר הקדוש ששיר השירים הינו סוד הסודות, הרזא דרזין של המרכבה העליונה[10] שעליו מדובר בפרק הראשון דיחזקאל. הרעיון העיקרי של המרכבה הוא שהוא מייצג את ענין הכניעה המלאה וההתבטלות המוחלטת לרצון הא-ל – כשם שלמרכבה אין רצון משלה, אלא הולך לכל מקום בו הרוכב מחליט לקחת אותו, כן הוא המרכה הרוחנית.

אולם במובן עמוק יותר, לא רק שהרכב (המרכבה בחזונו של יחזקאל) נכנע לרצון הרוכב, תוך שמירה במהותו על ישות מובחנת, אלא שהרכב הופך להרחבה של הרוכב – הוא כבר אינו גוף עצמאי המגשים את רצון הרוכב השולט בה, אלא היא המתמזגה עם הרוכב כדי להפוך לדבר אחד. זוהי המשמעות האמיתית של אמירת החכמים[11] כי “האבות – אברהם, יצחק ויעקב – הן הן המרכבה”. הם היו אלה שהתמזגו לראשונה עם הרצון האלוקי והביאו אותו להתגלות. וכן הוא הענין המרכזי בשיר השירים – התבטלות מוחלטת להקב”ה כמו מרכבה לרוכבו.

נראה כי זו גם תמצית ההצהרה בספר הבהיר[12]: “אמר ר’ יוחנן: כל הספרים קדושים וכל התורה קודש ושיר השירים קודש קדשים, ומאי ניהו קדש קדשים? אלא קודש הוא לקדשים” – לאלו שהם קדושים.

דבקות

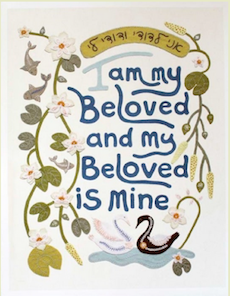

אחד הנושאים העיקריים של שיר השירים הוא הצמאון והכמיהה של הנשמה לדבוק באהובה. זה ידוע בתור ‘דבקות’ בלשון הקבלה, אם כי המונח עצמו מתבטא כהנחיה לכל אדם בתורה עצמה, “ואתו תעבדו ובו תדבקון” (דברים יג, ה). וכן הוא בעוד כמה פסוקים.[13]

הרב אברהם אבן עזרא מסביר כי השיר כולו הוא ביטוי של אהבה ומכיל סודות עליונים המשתרעים על פני כל מהלך ההיסטוריה, מאברהם אבינו ועד לעידן המשיח שיבוא במהרה בימינו, והוא מזהיר מפני פרשנות ביטויי האהבה שם ככל מה שקשור לתשוקה האנושית.

הרב עובדי’ ספרנו מוסיף כי שיר השירים נקראת קדש הקדשים כיוון שהיא מכוונת את לב האדם לאהבת אלוקים.

הרב אריה לייב אלתר, הידוע בשם ספרו ‘שפת אמת’, מסביר כי שיר זה עולה מדבקות הנשמה למקורו לעיל.[14]

אכן, השיר כולו הוא להסביר כי כל העניינים הארציים הם רק משל שבאמצעותה נוכל להבין את האהבה שעלינו לחוש לה’, שכן האדם צריך לדבוק בו, שהוא ית’ הוא הנמשל כביכול[15].

איש ואשה כמשל

זה מביא אותנו לשאלה הבלתי נמנעת – אם שיר השירים היא בעצם שיר הנפש בחיפושי’ה, ואכן הצמא להיות דבוק לה’, והיא מבטאת את הסודות והרזים העמוקים ביותר של התורה, מדוע השתמש שלמה המלך במשל של איש ואשה, חתן וכלה, ואהבה ביניהם כדי לתאר את הקשר הזה? לא היה מתאים יותר להשתמש במשל אחר, נניח זו של מורה ותלמיד?

למעשה, שאלה זו אינה שאלה חדשה, והוגשה על ידי מאור לא פחות מהבעל שם טוב לתלמיד המובהק ועורך הראשי של תורת האריז”ל, הרב חיים ויטאל במהלך עליית הנפש של הבעל שם טוב למרומים. כאשר שאל הבעל שם טוב את הרב חיים ויטאל מדוע השתמש במשל איש ואשה בהקלטת תיאור המציאות הרוחנית בתורתו של האריז”ל, הגיב רבי חיים בכך שהגיש לו קולמוס והציע לו את האפשרות לכתוב טוב יותר![16]

אבל אולי נוכל לתרץ – שאם הי’ נעשה שימוש במשל מורה / תלמיד, זה יכול היה להציע כי היחסים בין העם היהודי לה’ הם קשר רוחני גרידא, המתבטא בלימוד תורה ותפילה באופן בלעדי. כל מושג המצוות (מילוי המצוות שקיימות בעיקר עם הגוף הפיזי) היה נותר בחוץ. בהתאם לכך שלמה המלך השתמש במשל איש ואשה או חתן וכלה כדי לבטא את היחוד (האחדות עם ה’) שהושג באמצעות ביצוע מצוות, כמו גם באמצעות לימוד והתבוננות.

שיר

בזהר הקדוש מציין רבי שמעון בר יוחאי כי בכל התורה (חמשה חומשי תורה) המילה המשמשת ל’שיר’ היא שִׁירָה – בצורת נקבה, ואילו בשיר השירים בצורת זכר – שִׁיר. הוא מסביר שכל השירים בתורה מבטאים את שבחי ישראל על הקב”ה, ואילו שיר השירים מבטאת את שבח ה’ על ישראל. ולכן, כדברי ה’ (שהרי שה”ש הוא ‘לשלמה’ – להמלך שהשלום שלו) הרי זה בצורת זכר!

באופן דומה להנ”ל המדרש[17] מצהיר כי לעולם אין לפרש את שיר השירים במובן גנאי, אלא להיפך – כהלול. שכן שיר השירים ניתנה רק כדי לשבח את מעלות העם היהודי. מהן אותן מעלות? שהעם היהודי צמאים וכמהים – עד כדי ‘חולת אהבה’[18] – לדבוק באהובם, בהקב”ה[19], כאמור לעיל.

הזהר הקדוש מוסיף כי מטרת המשכן שעשה משה במדבר היתה כך שהשכינה תרד לארץ ותשכון במשכן, כפי שאומר הפסוק, “ועשו לי מקדש ושכנתי בתוכם” (שמות כה, ח). אך במקביל, הוקם משכן נוסף – למעלה. וכאשר בית המקדש הראשון נבנה [על ידי שלמה המלך] נבנה יחד אתו עוד אחד [– למעלה מעלה], וכך כל העולמות [העליונים והתחתונים] ישגשגו ויצליחו. העולם כאן למטה הפך לריחני [כלומר זהו סימן תיקונו] וכל השערים העליונים נפתחו, והאור זרח. מעולם לא הייתה שמחה כזו בעולם כמו באותו יום, ואלה שלמעלה [המלאכים] ואלה שלמטה [בני ישראל] שרו. זו הסיבה שאפשר לקרוא את התואר ‘שיר השירים’ כשִׁיר השָׁרִים – שיר הזמרים, השיר שמקהלת המלאכים מעלה שירה להקדוש ברוך הוא[20].

פרשנות התורה

ישנן ארבע גישות בסיסיות לפרשנות כתבי הקודש[21], המתמקדות במשמעות הפשוטה של הטקסט (פשט); רמיזות למשמעות עמוקה יותר (רמז); הגישה המוסרית או השיפור העצמי (דרוש), והגישה שמתמקדת על רזי התורה (סוד).

המדרש מצהיר כי “יש שבעים פנים לתורה”. הרב יצחק לוריא, הידוע יותר בשם אריז”ל, מציין כי ישנם 600,000 הסברים בכל אחת מארבע הגישות שהוזכרו לעיל[22]. הוא הוסיף כי מספר זה תואם את מספר שורשי הנשמות הקיימים בעם ישראל תמיד. לכן, פן מסוים של התורה מיועד, ובדרך כלל מושך, סוג מסוים של נשמה[23].

מסקנה לכך היא ש”את הכל עשה יפה בעתו” (קהלת ג, יא), כפי שמזכיר לנו שלמה המלך. חז”ל[24] מעירים על פסוק זה: אמר רבי יהודה בר’ סימון ‘ראוי הי’ אדם הראשון שתנתן התורה על ידו’ אלא שאמר ‘אם שש מצות נתנו לו ולא הי’ יכול לעמוד הבן ולשמרן… ולמי אמי נותן? לבניו’.

מובן מהנ”ל שהקדוש ברוך הוא ממנה זמן לכל מה שהוא עושה, וזה מה שאומר הפסוק “את הכל עשה יפה בעתו” – בזמן המתאים והכרחי לעניין זה. כך ניתן להבין שעד לבואו של אותו הזמן בו הרעיון הועלה לתורה על ידי תלמיד חכם מכובד, עדיין לא היה צורך במושג ולכן הוא לא נחשף! זה נכון בבירור לגבי תורת הזוהר שלא נתגלה עד המועד שהצטרכו לו.

אולם אין זה אומר שמישהו פטור מללמוד או לעסוק בכל חלקי התורה, שהרי “תורה אחת ומשפט אחד יהיה לכם ולגר הגר אתכם” (במדבר טו, טז). אעפ”כ כתב בעל התניא (באגה”ק פרק ז) ש”אף שגילוי זה ע”י עסק התורה והמצות הוא שוה לכל נפש מישראל בדרך כלל כי תורה אחת ומשפט א’ לכולנו אעפ”כ בדרך פרט אין כל הנפשות או הרוחות והנשמות שוות בענין זה לפי עת וזמן גלגולם ובואם בעוה”ז וכמארז”ל[25] אבוך במאי הוי זהיר טפי א”ל בציצית כו’ וכן אין כל הדורות שוין כי כמו שאברי האדם כל אבר יש לו פעולה פרטית ומיוחדת העין לראות והאזן לשמוע כך בכל מצוה מאיר אור פרטי ומיוחד מאור א”ס ב”ה. ואף שכל נפש מישראל צריכה לבוא בגלגול לקיים כל תרי”ג מצות מ”מ לא נצרכה אלא להעדפה וזהירות וזריזות יתירה ביתר שאת ויתר עז כפולה ומכופלת למעלה מעלה מזהירות שאר המצות. וזהו שאמר במאי הוי זהיר טפי טפי דייקא.

אכן המשמעות היא שפנים מסוימים של לימוד תורה מעוררים נשמות שונות בזמנים שונים, למרות שהתורה כולה ניתנה למשה בסיני, כפי שקובעו חז”ל[26] שכל מה שתלמיד ותיק עתיד לחדש כבר ניתן למשה מסיני!

פרשנות הזהר

הרמב”ן כותב במבואו לשיר השירים כי השיר כולו מכוסה במונחים של משל –וחובתנו היא לנסות להבין את הנימשל. כלומר, מה שרומזת המשל במובנה העמוק ביותר. כדוגמה הוא מביא את הפסוק (שה”ש א, ב) “ישקני מנשיקות פיהו” ומבאר ש”נשיקה” כאן היא משל לדביקות – הדבקת הנפש למקור שלה, כפי שהזכרנו לעיל.

אכן גם הזהר מעמיד פנים דומים להנ”ל: כל תורתו של שלמה המלך לבושה בעניינים אחרים, ממש כמו סיפורי אירועים שהתרחשו בעולם הזה. יתר על כן, כל מה ששלמה אמר [בכל חיבוריו שיר השירים, משלי, קהלת] הכל הוא חכמה נסתרה”.[27]

יש שפע של פרשנויות לשיר השירים שמתעמקות במשמעות העמוקה יותר של משלים ורמיזות אלה. בין פרשנויות אלה, אחד מהם התעלם מעיני הקהל הרחב בעיקר בשל קושי השפה ומורכבות מחשבתה – פרשנותו של הזוהר הקדוש.

הזהר הוא ייחודי בקרב פרשנויות במובן זה שהוא לא רק מתענג על המימד הסודי, אלא הוא “המקור לכל התורות הקבליות הסמכותיות המאוחרות יותר של חוגו של האריז”ל ואחרים … יתר על כן, המקובלים[28] מייחסים כוח מיוחד ללימוד הזהר בכך שלימוד זה מבטל גזירות רעות, מקל על הגלות, מזרז את הגאולה, ומוציא שפע אלוקית וברכות”.[29]

הזוהר התגלה לראשונה בשליש האחרון של המאה השלוש עשרה בלוח הלועזי. אחד המקובלים המובילים של היום, הרב משה דה ליאון (1238-1305), גילה כתבי יד קדומים שככל הנראה נתחברו על ידי התנא של המאה השנייה למנינם רבי שמעון בר יוחאי וחוג תלמידיו, ונכתבו ע”י אחד מתלמידיו המובהקים, רבי אבא. הרב משה החל להפיץ עותקים של הטקסט למקובלים מובילים אחרים.

הונחה כי רבי שמעון בר יוחאי, אחד מרבותיו של רבי יהודה הנשיא[30], ותלמידיו הקדישו את המסורת הסודית לכתיבה מאותן הסיבות שרבי יהודה הנשיא הקדיש את המשנה לכתיבה – לחשש שיאבדו עקב הצרות הרבות שעברו על ראשים של בני ישראל בעת ההוא. חיבורים אלה הועברו לאחר מכן ליורשיו של רבי שמעון ולראשי המעגל הקבלי שלו. עם זאת, בניגוד למשנה, כתבים אלה לא נועדו לפרסום ואף לא להפצה נרחבת, בהתאם לאופי הסודי של המסורת הקבלה. במקום זאת הם הועברו בכל דור לקומץ תלמידים שנבחר בקפידה בלבד עד שהגיעו לרב משה דה ליאון.

בין חכמי הקבלה היו אלו שאמרו שהרמב”ן בעצמו, שהוא הי’ מקובל מפורסם, שלח אותם מישראל בספינה לבנו בקטלוניה, אך הספינה הוסטה והטקסטים הגיעו לידי הרב משה דה ליאון[31].

אחרים הסבירו כי כתבי היד הללו הוסתרו בכספת במשך אלף שנה והתגלו על ידי מלך ערבי ששלח אותם לטולידו לפענוח. היו שטענו כי כובשי ספרד גילו את כתבי היד של הזוהר בקרב רבים אחרים בספרי’ בהיידלברג, גרמני’. הסברים אחרים הוצעו גם כן[32].

באיזה אופן שהטקסטים הגיעו לידי הרב משה דה ליאון אין זה העיקר אצלינו, כי על פי מקורות וסמכויות יהודיים מסורתיים אין ספק שרבי שמעון בר יוחאי וחוג תלמידיו חיברו את הזהר והתקבלו הכתובים בתוך המסורת שלנו עד כי רבות מתורתו של הזוהר שולבו במשפט ובמסורת היהודית[33].

רבי שמעון בר יוחאי היה אחד מהתנאים הגדולים שחיו בתקופת הרדיפה הרומית. הוא היה אחד התלמידים המובהקים של רבי עקיבא, שאמר לו, “דייך שאני ובוראך מכירין כוחך”[34].

רבי שמעון הי’ מלומד בניסים, ולכן נשלח על ידי מנהיגי העם היהודי לרומא כדי לנסות להסיר את האיסור על לימוד התורה וקיום מצוותה באופן רשמי על ידי קיסר התקופה (אנטונינוס פיוס). התלמוד[35] מספר כי בתו של הקיסר הייתה מוחזקת על ידי שד, שרבי שמעון גרש. האיסור בוטל לאחר מכן.

עם זאת, בסביבות שנת 149 למספרם נאלץ רבי שמעון עצמו לברוח מהשלטונות הרומאים. אחד ממכריו שיבח את הרומאים על מאמציהם ליזום ולסדר חיי המסחר והחברה בישראל. רבי שמעון התנגד לעמדה זאת וקבע כי כל מה שתקנו לא תקנו אלא לצורך עצמן. דבר הדיון הזה הגיע לרשויות הרומיות, שהכריזו כי רבי שמעון יהרג. רבי שמעון ברח והסתתר במערה שלוש עשרה שנה יחד עם בנו רבי אלעזר, ושם למדו תורה יומם ולילה. באורח פלא הם נשמרו על ידי פרי עץ חרוב ומים ממעיין עד שמת הקיסר והגזר הדין עליהם בוטל[36].

במהלך שהותו במערה חיבר רבי שמעון ככל הנראה את הגופה המרכזית של הזוהר שתוארה כ”חבורא קדמאה”[37] – ‘המשנה הראשונה’ של הזהר. יתרת תורתו הועברה בעל פה לתלמידיו ולתלמידיהם, והם העבירו הרבה מתורתו לכתיבה, ככל הנראה במשך תקופה של כמה דורות[38].

בחרתי כמה מפרשנויות הזוהר על סמך גישתם הייחודית לשיר השירים – הממד הסודי. וביניהם בחרתי רק את הקטעים המאירות את שיר השירים באור חדש – תיאור ייחודי של הגישה הקבלית והעלאה הרוחנית שהוא מעורר.

התרגום שלנו

ההבנה של הזוהר ברבים מהפסוקים שונה מאוד מההבנה של מרבית הפרשנים, אפילו אותם פירושים שניגשים לטקסט מנקודת מבט מדרשית. תרגום פשוט של פסוקי שיר השירים יהפוך את רבים מהחידושים של הזוהר בהבנת המקרא לכמעט בלתי אפשריים להבנה. לפיכך, ניסינו לתרגם את הפסוקים מנקודת מבטו של הזוהר כמיטב יכולתנו, במיוחד לאור המגבלות של השפה האנגלית לבטאות חכמת האלקות, בהשוואה ללשון הקודש (כוונתי היא שמילים בעברית הן לרוב רב ממדיות, ואילו באנגלית הן בדרך כלל חד-ממדי).

בעיה נוספת שעמדה בפנינו בתרגום שיר השירים לאנגלית היא שתרגום לפרוזה רגילה יפגע ברצינות בשירה ובהרגשות העמוקות שהפסוקים מבטאים. אז שוב, כמיטב יכולתנו, ניסינו ‘לייצר’ את האנגלית בצורת ‘שירה’ על ידי עיבוד חוזר של מבנה המשפטים (אך לא את התוכן) על מנת להשיג תוצאות שיש להם יופי וחן מעט יותר קרוב למשמעותם בלשון הקודש. במובן זה, כנראה לקחנו ‘רשיון המחברים’ כלשהו בתרגום שלנו, אך אנו מאמינים שהתוצאה הסופית נשארת נאמנה לכוונתו של הזוהר, כמו גם ליצירת השיר המדהים הזה של שלמה המלך.

משה מילר

ה’ נמחם אב, תשפ”א

[1] סנהדרין פו, א: “אמר ר’ יוחנן סתם מתני’ ר’ מאיר סתם תוספתא ר’ נחמיה סתם ספרא רבי יהודה סתם ספרי ר”ש וכולהו אליבא דרבי עקיבא” – ממה שלמדו מר’ עקיבא אמרום (רש”י).

[2] תנחומא פ’ תצוה, פ”ה.

[5] שו”ע או”ח סימן רפח, ס”ק ב.

[6] תורת מנחם חט”ז ע’ קכו.

[8] זהר ח”ב יח, א: ושלמה זכה יותר באותו השיר, וידע החכמה, ואזן וחקר ותקן משלים הרבה, ועשה ספר מאותו השיר ממש, והיינו דכתיב (קהלת ב ח) עשיתי לי שרים ושרות, כלומר קניתי לי לדעת שיר מאותן השרים העליונים, ואשר תחתם, והיינו דכתיב שיר השירים, כלומר שיר של אותם שרים של מעלה, שרים.

[9] זהר חדש (מרגוליות) סא, ב. (ובדפוס הרגיל ע’ עה, ב).

[10] זהר חדש שם, וז”ל: ” הא הכא רזין דרתיכא קדישא עילאה, דארבע שמהן גליפן, והא איהו רזא דרזין רתיכא עילאה דשמהן”.

[11] בראשית רבה מז, ו; פב, ו ועוד; זהר ח”א רי, ב; ח”ג קפד, ב.

[12] ספר הבהיר פ’ קעד.

[13] לדוגמא: דברים י, כ “אתו תעבד ובו תדבק“; שם ל, כ: “…לאהבה את ה’ אלקיך לשמע בקלו ולדבקה בו“.

[14] שפת אמר, פסח תרנ”ה.

[15] שפת אמר, פסח תרס”א.

[16] ראה מגדל עוז (מונדשיין) ע’ 372.

[17] שה”ש רבה ב, יג.

[18] שה”ש ב, ה: סַמְּכוּנִי בָּאֲשִׁישׁוֹת רַפְּדוּנִי בַּתַּפּוּחִים כִּי חוֹלַת אַהֲבָה אָנִי.

[19] ראה הרב צדוק ‘רסיסי לילה’ יז, ע’ 19.

[20] זהר ח”ב ע’ קמג, א.

[21] ראה שער הגלגולים להאריז”ל, הקדמה יא, טז.

[22] שער הגלגולים, הקדמה יז; לקוטי הש”ס מהאריז”ל סדר האלפא ביתא.

[23] אריז”ל שער רוח הקודש, הקדמה ג בשם ספר הבהיר סעיף נא.

[24] קהלת רבה ג, יא.

[25] שבת קיח, ב.

[26] ראה מגילה יט, ב; שמות רבה רפמ”ז.

[27] ראה זהר ח”א ע’ קצה, א; שם, רכג, ב; זהר ח”ג ע’ קנז

[28] ראה הרב אברהם אזולאי הקדמה לאור החמה ע’ ב, ד.

[29] מהמלצתו של הרב דר. עמנואל שוחאט לספרי Zohar, Bereishit 1

[30] רמב”ם בהקדמתו למשנה תורה.

[31] שם הגדולים, חיד”א ספרים, ז, ח.

[32] שם.

[33] כתבתי מספר מאמרים הבוחנים לעומק את תיאוריות המחבר השונות, ומפריך את אלו הטוענים כי רבי שמעון לא כתב את הזוהר. בקצרה, טענותיהם של אלה הטוענים כי הזוהר נכתב על ידי משה דה ליאון נותרות ללא יסוד כלל.

[34] ירושלמי סנהדרין ו, ב.

[35] מעילה יז, א-ב.

[36] שבת לג, ב.

[37] זהר ח”ג ע’ ריט, ב.

[38] רבי אברהם זכותא, ספר היחוסין ‘רבי שמעון בר יוחאי’, הובא בהקדמתו של הרב אברהם אולאי באור החמה ע’ כד. וראה גם סדר הדורות ‘רבי שמעון בר יוחאי’.

INTRODUCTION

SHIR HASHIRIM – HOLY OF HOLIES

Shir Hashirim – Song of Songs – assumes a special place in Jewish Scripture. Although it is one of twelve works in the category of sacred writings (Ketuvim), the great Sage Rabbi Akiva[1] declared: “The world was not worthy of the day that Shir Hashirim was given to the Jewish People.”[2] Furthermore, Rabbi Akiva added, “all sacred writings are holy, but Shir Hashirim is the holy of holies!”[3]

The Midrash[4] proposes an analogy to help us understand Rabbi Akiva’s words: Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya said, “To what can this be compared? To a king who took a large measure of wheat and gave it to the royal baker whom he told ‘[grind it and then] remove from it this amount of fine flour, this amount of rough bran, this amount of fine brand, and then sift out the finest and highest quality flour – just enough to make a single loaf. Similarly, all of the sacred writings are holy, but Shir Hashirim is the holy of holies…” It is the most distilled and refined Divine wisdom there is.

The Zohar[5] then asks that if this is so – if Shir Hashirim is so supremely holy – why is it not counted among the books of the Prophets (Nevi’im), rather than among the Sacred Writings (Ketuvim)? The Zohar answers that since it is a song of praise sung by the Community of Israel – the level of malchut among the sefirot – it belongs in Ketuvim, which is the level of malchut. But malchut is ultimately the crown of the King, as in the verse, “A woman of valor (malchut) is the crown of her Husband” (Proverbs 12:4).

The Zohar[6] adds that the day on which Shir Hashirim was revealed, was the day that the Shechinah (Divine Presence) descended into the Temple, thus fulfilling the entire purpose of Creation.[7]

THE ENTIRE TORAH

Although Shir Hashirim is only eight chapters long, and fairly short ones at that, the Zohar[8] declares that it is the fundamental principle of the entire Torah, the fundamental principle of Creation, the fundamental principle of the secret of the Patriarchs, the fundamental principle of the exile in Egypt, and of the Exodus from Egypt, and of the Song by the Sea (Exodus chap. 15). It is the fundamental principle of the Ten Commandments and Mount Sinai where they received them, the fundamental principle of the entire journey of the Israelites through the desert until they came to the Holy Land and built the Temple. It is the fundamental principle of crowning the supernal holy Name with love and joy, the fundamental principle of the exile of the Jewish People among the nations of the world, and their redemption from that situation. It is the fundamental principle of the Resurrection of the Dead until the day that is called “a Sabbath unto God,” and of what is and what was and what will be in the seventh millennium. All of this is in Shir Hashirim![9]

Where did King Solomon learn all this from? Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai taught that he acquired all the knowledge contained in Shir Hashirim from the supernal angels. Accordingly, do not read the title as Shir Hashirim, but rather as Shir Hasarim – the Song of the Mighty Angels above… it is the Song that the Sarim – the holiest angels – sing.[10]

Indeed we find that when the mystical secrets of Shir Hashirim became revealed to Rabbi Akiva, his eyes flowed with tears.[11] This was because the Divine revelation in Shir Hashirim is greater than the mind – even the mind of Rabbi Akiva – can contain.[12]

It is not surprising therefore that Shir Hashirim is regarded as the holy of holies.

MERCAVA

Lest one think that Shir Hashirim provides us only with the text as a lofty but hidden treasure, but not with the keys to open it, the Zohar[13] extols the virtues of that generation in which supernal wisdom was revealed[14] – referring to Shlomo Hamelech, King Solomon. When He wanted to reveal the secrets of Shir Hashirim on earth – secrets that He did not reveal even to the supernal angels i.e. the secret wisdom of the supernal Ineffable Name and all the holy Names that derive from it – He revealed them to King Solomon. At that time the angels declared, “…how mighty is Your Name throughout the earth” (Psalms 8:2).

Elsewhere the Zohar[15] declares that Shir Hashirim is the secret of the supernal Mercava (literally, ‘the Divine Chariot’ – the ‘vehicle’ so to speak for Divine revelation, discussed in the first chapter of Ezekiel). The primary concept of the Mercava is that it represents the idea of complete submission to the will of God, just as a chariot has no will of its own, but goes wherever the rider decides to take it.

In a deeper sense though, it is not merely that the vehicle (the chariot in Ezekiel’s vision) submits to the will of the rider, while remaining in essence a distinct entity, but rather that the vehicle becomes an extension of the rider – it is no longer an independent entity fulfilling the will of the rider controlling it, but rather it has merged with the rider to become one thing. This is the real meaning of the statement of the Sages[16] that “the Patriarchs – Abraham, Isaac and Jacob – are the Mercava.” They were the ones who first merged with the Divine Will and brought it into revelation.

DEVEIKUT – CLEAVING OF THE SOUL

One of the primary themes of Shir Hashirim is the longing of the soul to cleave to its Beloved. This is known as deveikut in more modern terminology, although the term itself is expressed as a directive to every individual in the Torah itself – “…Him you shall serve, and to Him you shall cleave” (Deuteronomy 13:5). There are several other verses that express a similar sentiment.[17]

The Ibn Ezra[18] explains that the entire Song is an expression of love and contains supernal secrets spanning the entire course of history, from Abraham until the future Messianic era, and he warns against interpreting the expressions of love there as anything akin to human passion.[19] The Sforno[20] adds that Shir Hashirim is called the holy of holies because it orients the heart of man to love of God.

Rabbi Aryeh Leib Alter,[21] better known by the title of his commentary on the Torah, the Sefat Emet explains that this song emerges from the soul’s deveikut to its source above.[22]

And indeed, the entire Song is to explain that all earthly matters are only an analogy by which to understand the love that we should feel for God, for man needs to cleave to Him to whom the analogy always refers.[23]

This seems to also be the gist of the statement in the Sefer Habahir[24] that Shir Hashirim is the holy of holies – i.e. it is holy to those who are holy.

THE MALE‑FEMALE ANALOGY

This brings us to the inevitable question: if Shir Hashirim is essentially a song of the soul in its quest, and indeed thirst, to cleave to God, and it expresses the deepest mystical secrets of the Torah, why did King Solomon use the analogy of male and female love and intimacy (zivug) to depict this relationship? Would it not have been more appropriate to use another analogy, say that of a teacher and student?[25]

In fact, this question is not a new one, and was posed by no less a luminary than the Ba’al Shem Tov (1698-1760) to the chief recorder and redactor of the Arizal’s teachings, Rabbi Chaim Vital (1543-1620) during one of the Ba’al Shem Tov’s ‘soul-ascents’ on high. When the Ba’al Shem Tov asked why he used such pervasive sexual metaphors in recording the Arizal’s description of spiritual reality, Rabbi Chaim responded by handing him a quill and offering him the opportunity to write better.[26]

Perhaps we could answer that if the teacher/student analogy would have been used, this could have suggested that the relationship between the Jewish People and G-d is a purely spiritual one, expressed through Torah study and prayer exclusively. The entire concept of mitzvot (fulfilling the commandments which are primarily with the physical body) would have been left out. Accordingly King Solomon used the male/female intimacy analogy to express the yichud (oneness with God) achieved through the performance of mitzvot, as well as through study and meditation.

SONG

In the Zohar, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai notes that throughout the Torah (the five Books of Moses) the word used for ‘song’ is שִׁירָה (shirah)[27] – in the feminine form, whereas Shir Hashirim is in the masculine form – שִׁיר (shir). He explains the all the songs in the Torah express the Jewish People’s praises of God, whereas Shir Hashirim expresses God’s praise for the Jewish People, and therefore – as God’s words – it is in the masculine form![28]

In similar fashion, the Midrash[29] declares that Shir Hashirim should never be interpreted in a derogatory sense, but just the opposite – as praise. For Shir Hashirim was given only to extol the virtues of the Jewish People.

And what are those virtues? That the Jewish People yearn passionately – to the point of love-sickness – to cleave to their Beloved,[30] as mentioned above.

The Zohar adds that the purpose of the Tabernacle Moshe made in the desert was so that the Shechinah (the Divine Presence) would descend to earth [and reside in the Tabernacle, as the verse states, “Make for Me a Temple and I will dwell among them” (Exodus 25:8)]. But at the same time, anther Tabernacle was erected – up above. And when the First Temple was built [by King Solomon] another one was built together with it [– up above], and thus all the worlds [upper and lower] would thrive. The world [down here] became fragrant [i.e. it was rectified] and all the supernal gates were opened and the light shone forth. There was never such joy in the world as on that day, and those up above [the angels] and those down below [the Israelites] sang. This is why the title ‘Shir Hashirim’ (the Song of Songs) can be read as Shir Hasharim – the Song of the Singers, the song that the angelic choir up above sings to the blessed Holy One.[31]

SCRIPTURAL EXEGESIS

There are four basic approaches to Scriptural exegesis,[32] focusing on the plain meaning of the text (peshat); allusions to a deeper meaning (remez); the homiletic or self-improvement approach (drash), and the esoteric (sod). The Midrash[33] declares that, “there are seventy facets of Torah.” Rabbi Isaac Luria, the famed 16th Century kabbalist from Safed, better known as the Arizal, mentions that there are 600,000 explanations in each of the four approaches mentioned above.[34] He added that this number corresponds to the number of soul-roots that are extant among the Jewish People at any one time. Therefore, a particular facet of Torah is designed for, and generally appeals to, a particular type of soul.[35]

A corollary of this is that “He made everything beautiful in its time” (Ecclesiastes 3:1), as King Solomon reminds us. The Sages comment on this verse that by rights the Torah should have been given to Adam… But the Holy One, blessed is He, reconsidered the matter and said, ‘…I will give it his descendants.’ For the Holy One, blessed is He, appoints a time for everything He does, and this is what the verse means by ‘beautiful in its time’ – a time which is appropriate, relevant and necessary for this matter. Thus it can be understood that until the arrival of that time in which the idea came to be introduced into Torah by a distinguished scholar, there was as yet no need for the concept, and therefore it was not revealed!” This is clearly true of the teachings of the Zohar.

This does not mean, however, that anyone is excused from studying or practicing all aspects of Torah, since “there is but one Torah and one judgment, for you and for the convert who dwells among you.”[36] Nevertheless, the author of Tanya, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi explains: “More specifically, not all souls[37] are equal in this regard, and it depends on the circumstances and time of their incarnation and entry into this world; and as our Sages, of blessed memory, said: ‘with what [mitzvah-commandment] was your father most careful? He answered him – with [the commandment of] tzitzit….’[38] Likewise not all the generations arc the same. For just as with the organs of man every organ has its own, particular and distinctive function, the eye to see and the ear to hear, so, too, through each commandment there radiates a particular and distinctive light from the light of the blessed Ein Sof [the Infinite One]. And although every Jewish soul needs to be reincarnated in order to fulfil all the 613 commandments, even so, special attention to a particular mitzvah is necessary only for the sake of an additional measure of vigilance and enthusiasm – exceedingly uplifting and powerful – and far surpassing the enthusiasm he has for [fulfilling] other commandments. And that is what he meant when he said, ‘with what was he most careful?’[39]

What it does mean is that certain aspects of Torah study appeal to different souls at different times, even though the entire Torah was given to Moses at Sinai, as the Talmud states, “All innovations of future distinguished scholars were already given to Moshe at Sinai.”[40]

THE ZOHAR’S COMMENTARY

The Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman Gerondi 1195-1270), also known as Nachmanides, writes in his Introduction to Shir Hashirim that the entire song is couched in terms of a mashal – a metaphor – and our duty is to attempt to understand the nimshal i.e. what the metaphor alludes to in its deepest sense. As an example he cites the verse (1:2) יִשָּׁקֵנִי מִנְּשִׁיקוֹת פִּיהוּ – “He will kiss me, from His mouth to mine,” in our translation. Ramban explains that ‘kissing’ here is a metaphor for deveikut – the cleaving of the soul to its source, as we mentioned above.

Indeed, the Zohar [41] expresses the same view: “All of Shlomo’s (King Solomon’s) teachings are clothed in other matters, just like many Torah teachings which are clothed in stories of events that took place in this world.” Furthermore, “Everything Shlomo said [in all of his works Song of Songs, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes] is all hidden wisdom.”[42]

There are a wealth of commentaries on the Song of Songs (including the Ramban’s) that delve into the deeper meaning of these metaphors and allusions. Among these commentaries, one in particular has been largely overlooked due to the difficulty of the language and the complexity of its thought – the Zohar’s commentary. The Zohar is unique among commentaries in the sense that it not only revels in the mystical dimension, it is the “source of practically all the later authoritative Kabbalistic teachings of the school of Rabbi Isaac Luria and others… Moreover, the mystics[43] ascribe special potency to the study of the Zohar: it effects a nullification of evil decrees, eases the galut (exile), hastens the redemption, and draws forth Divine effluence and blessings.”[44]

The Zohar first came to light sometime in the last third of the thirteenth century. One of the leading kabbalists of the day, Rabbi Moshe de Leon (1238-1305), had discovered or had somehow come to possess ancient manuscripts, purported to have been written by the Second Century Tanna[45] Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his circle of disciples. Rabbi Moshe began disseminating copies of the text to other leading kabbalists.

It was conjectured that Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, one of the teachers of Rabbi Yehudah HaNassi,[46] and his disciples had committed the esoteric tradition to writing for the same reasons that Rabbi Yehudah HaNassi had committed the Mishnah to writing. These texts were subsequently handed down to Rabbi Shimon’s successors and the leaders of his Kabbalistic circle. However, unlike the Mishnah, these writings were not intended for publication, nor even for widespread dissemination, in keeping with the esoteric nature of the Kabbalistic tradition. Instead, they were passed down in each generation to a mere handful of carefully selected disciples until they reached Rabbi Moshe de Leon. Some believed that the Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman 1194-1270, himself a renowned Kabbalist) had sent them from Israel by ship to his son in Catalonia, but the ship had been diverted and the texts ended up in the hands of Rabbi Moshe de Leon.[47]

Others explained that these manuscripts had been hidden in a vault for a thousand years and had been discovered by an Arabian king who sent them to Toledo to be deciphered. Some maintained that Spanish conquistadors had discovered the manuscripts of the Zohar among many others in an academy in Heidelberg.[48] Other explanations have also been offered.

However the texts came to be in the possession of Rabbi Moshe de Leon, according to traditional Jewish sources and authorities, there is no doubt that the Zohar was authored by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his circle of disciples.[49] Many of the teachings of the Zohar have been incorporated into Jewish law and philosophy.

Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai was one of the great Tannaitic sages who lived during the era of Roman persecution (2nd century). He was one of the foremost students of Rabbi Akiva, who had said to him, “Let it be sufficient that I and your Creator know of your powers.”[50] He was also one of the teachers of Rabbi Yehudah HaNassi.[51]

Rabbi Shimon was well-versed in miracles, and was therefore sent by the leaders of the Jewish people to Rome to attempt have the ban on Jewish observance officially lifted by the emperor of the time (Antoninus Pius). The Talmud tells that the daughter of the emperor was possessed by a demon, which Rabbi Shimon exorcised. The ban was subsequently abrogated.[52] However, around the year 149 C. E. Rabbi Shimon himself was forced to flee from the Roman authorities. An acquaintance of his had privately praised the Romans for their efforts in initiating and organizing aspects of commercial and social life in Israel. Rabbi Shimon countered that they had done so merely out of self-interest. Word of this discussion reached the Roman authorities, who declared that Rabbi Shimon be put to death. He fled and hid in a cave for thirteen years together with his son Rabbi Elazar, where they studied Torah day and night. They were miraculously sustained by the fruit of a carob tree and water from a spring until the emperor died and the sentence upon them was annulled.[53]

During his stay in the cave, Rabbi Shimon apparently wrote the main body of the Zohar, which was described as “the First Mishnah.”[54] The remainder of his teachings was passed on orally to his disciples and to their disciples, and they committed many of his teachings to writing, probably over a period of several generations.[55]

I have selected some of the Zohar’s commentaries based on their unique approach to this text – the mystical dimension. And even in the Zohar, I have selected only those commentaries that illuminate the Song of Songs with a new light – a unique description of mystical methodology and the spiritual ecstasy that it engenders.

OUR TRANSLATION

The Zohar’s understanding of many of the verses is very different from that of the understanding of most commentaries, even those commentaries that approach the text from a Midrashic perspective. A straightforward translation of the verses of Shir Hashirim would therefore make many of the nuances highlighted in the Zohar almost impossible to understand. Accordingly, we have attempted to translate the verses from the Zohar’s perspective as best we could, particularly given the flatness of the English language compared with Hebrew (by this I mean that words in Hebrew are often multi-dimensional, whereas in English they are generally one-dimensional).

Another problem we faced in translating Shir Hashirim into English is that a translation into plain prose would detract seriously from the poetry and passion of the verses. So again, as best we could, we have attempted to ‘poeticize’ the English by reworking the structure of the sentences (but not the content) in order to achieve a somewhat more lyrical and graceful effect. In this sense, we have probably taken some poetic license in our translation, but we believe the end result stays true to the intention of the Zohar, as well as to King Solomon’s incredible masterpiece.

Rabbi Moshe Miller

5th Menachem Av 5781.

[1] About whom the Talmud (Sanhedrin 86a) states that virtually the entire Oral Law is according to Rabbi Akiva.

[2] Mishnah,Yadayim 3:5.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Tanchuma, Tetzaveh para. 5.

[5] Vol II, Terumah p. 144a.

[6] Vol II, Terumah p. 143b.

[7] Midrash Tanchuma, Bechukotai 3; Naso 16; Bereishit Rabba 3 (end) etc.

[8] Vol II, Terumah p. 144a.

[9] The Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman Gerondi 1195-1270), also known as Nachmanides, writes in his Introduction to the Song of Songs that even the destruction of the two Temples (the first of which King Solomon built) and the subsequent exiles the Jewish People suffered, are also hinted at in Shir Hashirim, but are not stated explicitly, since these tragic events should not be mentioned openly in song.

[10] Zohar II, 18b.

[11] Zohar I, 98a; Taz, Shulchan Aruch Orach Chaim s.k. 102 in the name of the Zohar Chadash.

[12] Torat Menachem vol. 16, p. 126.

[13] Zohar Chadash, Shir haShirim 61b (Margolis edition), 75b regular edition.

[14] See I Kings 3:28: “…they saw that the wisdom of God was within him.”

[15] Zohar Chadash, Shir haShirim 60b (Margolis edition), 74b regular edition

[16] Bereishit Rabba 47:6; Zohar I, 210b; Zohar III 184b.

[17] Deuteronomy 10:20; 30:20; 4:4.

[18] Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra, c 1092-1167, Spain.

[19] In his introduction to Shir Hashirim.

[20] Rabbi Ovadiah Sforno c 1475-1550, Italy.

[21] 1847-1905.

[22] Sefat Emet, Pesach 5655.

[23] Sefat Emets, Pesach 5631.

[24] Bahir 174.

[25] In a story told by Rabbi Ze’ev Greenglass, Rabbi Itche haMasmid Gurevitch once wondered why King Solomon used the analogy of the love of a man and woman to portray the love of the soul for God. Had King Solomon been a Hasid, Rabbi Itche mused, he would probably have used the analogy of the love of a Rebbe and Hasid.

[26] See Migdal Oz (Mondshein) p. 372 in the name of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Lubavitch, the Tzemach Tzedek; ‘Apples from the Orchard’ (Wisnefsky) Intro. p. xiii.

[27] E.g. Exodus 15:1; Numbers 21:17; Deuteronomy 31:19, 21, 30; ibid. 32:44.

[28] Zohar Chadash (Margolis) 62b. See also Metzudat David (Radbaz) Mitzvah 83.

[29] Shir Hashirim Rabba 2:13.

[30] See Rav Tzadok, Resisei Layla 17, p. 19.

[31] Zohar II, 143a.

[32] Rabbi Isaac Luria (1534-1572 CE) in Sha’ar HaGilgulim, Introduction 11, 16.

[33] Midrash Rabba, Bamidbar 13:15; Otiot d’Rabbi Akiva in Batei Midrashot, part 2. Midrashic literature was compiled between the 4th and 12th Centuries, primarily from earlier oral traditions.

[34] Sha’ar HaGilgulim, Introduction 17; Likutei Shas, Seder HaAlpha Beta.

[35] See Arizal, Sha’ar Ruach Hakodesh, Hakdama 3 (p. 38b) where he cites Sefer Habahir 51.

[36] Numbers 15:16. See Tanya chap. 44; Iggeret Hakodesh chap. 7.

[37] Specifically, he delineates the three lower levels of soul: nefesh, ruach, neshamah, roughly physical consciousness, emotional consciousness, and conceptual consciousness (albeit that these translations are of limited value).

[38] Tzitit are the Biblically mandates fringes worn on the corners of a four-cornered garment (see Deuteronomy 11:13-21).

[39] Talmud Shabbat 118b.

[40] Megillah 19b.

[41] Zohar III, 155b.

[42] Zohar I, 195a, 223a; Zohar III, 157a, 177b, 182a.

[43] See R. Abraham Azulay, Foreword to the Ohr Hachamah, p. 2d.

[44] From Rabbi Dr. Immanuel Schochet’s Approbation to my Zohar, Bereishit 1 (Fiftieth Gate Publications), a translation and commentary on the first 21 chapters of Genesis.

[45]. Sage of the Mishnaic era.

[46]. Rambam Intro. Ibid.

[47]. Shem HaGedolim, Chida Sefarim, Zayin, 8.

[48]. Shem HaGedolim, ibid.

[49]. The translator has written a number of articles which examine the various theories of authorship in depth, refuting those which maintain that Rabbi Shimon did not write the Zohar. In brief, the claims of those who maintain that the Zohar was written by Moshe de Leon remain largely unsubstantiated.

[50]. Yerushalmi Sanhedrin 6b.

[51]. Rambam Intro. Ibid.

[52]. Me’ilah 17a-b.

[53]. Shabbat 33b.

[54]. Chabura Kadmaa mentioned in Zohar III, p. 219a.

[55]. Rabbi Abraham Zaccuta, Sefer Hayuchasin ed. Philipowski, s.v. R. Shimon bar Yochai, p. 45a, cited by R. Abraham Azulay, Foreword to the Ohr Hachamah, p. 2d.; and see also R. Yechiel Heilperin, Seder Hadorot s.v. R. Shimon bar Yochai.